Catassembly: A Strategy towards Complex Assembly Systems

One important objective of molecular assembly research is to create highly complex functional molecular systems capable of responding, adapting, and evolving. Compared with living systems, the artificial systems are still rather primitive and are far away from realizing these features. Nature is by far the most important source of inspiration for designing and creating such systems. It has been shown that the assembly of many biological complexes is ‘‘catalysed’’ by other molecules, such as molecular chaperones, rather than relying solely on self-assembly.

The concept of “catassembly”

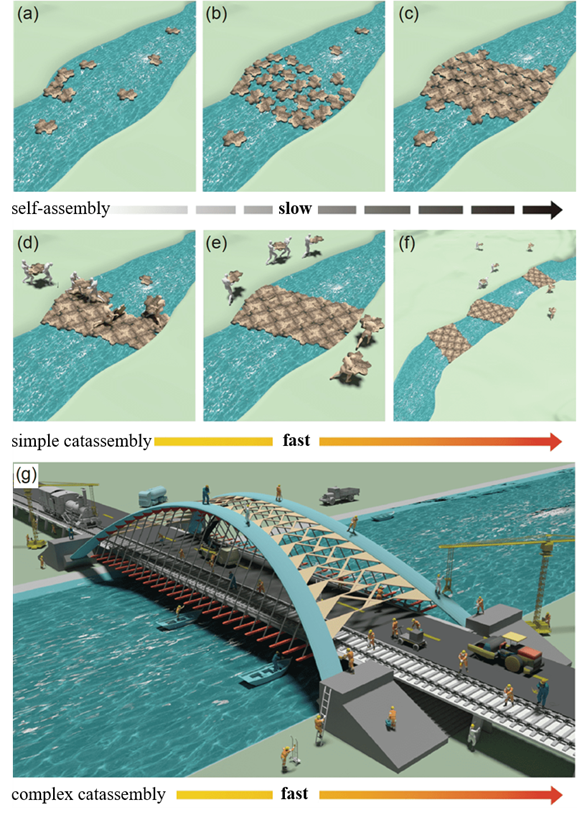

Drawing inspiration from catalysis in chemistry, we pioneered the concept of “catassembly” as a new strategy towards the construction of complex assembly systems. It proposes to employ catassemblers (molecules or assemblies) act as “catalysts” for the assembly process. The catassemblers can accelerate the assembly and/or guide it towards a specific pathway, i.e., high efficiency and/or selectivity. Once the assembly is complete, the catassemblers are absent from the final product. The verb and adjective forms of catassembly are “catassemble” and “catassembled” (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Cartoons of the construction of a floating bridge that illustrate why catassembly is more efficient than self-assembly. Panels a to c represent a self-assembly process, which requires many hours to form a floating bridge. In contrast, with the assistance of porters and builders (corresponding to two kinds of catassemblers), a bridge can be built in 1 hour (panels d and e). After the first bridge is completed, the workers leave it and build other bridges somewhere else (panel f). The more complex the assembly, the more catassembly is required (panel g). To build a complex, multi-functional bridge requires the collaborative work of many workers (such as builders, sentries, transporters, coordinators etc.). Multiple catassemblers are required with varying participation timelines and functions for complex assembly systems.

The significance of catassembly in molecular assembly mirrors that of catalysis in chemical reactions. While simple assembly relies on spontaneous interactions among assembly units, achieving complex assemblies with multiple steps and pathways through spontaneous assembly alone is nearly impracticable. Therefore, assisted assembly strategies such as catassembly are indispensable. Indeed, the construction of intricate biological assemblies extensively employs catassembly strategies, leveraging the synergy of matter, energy, and information. Consequently, the concept and techniques of catassembly are poised to play a pivotal role in propelling artificial molecular assembly from simplicity to complexity.

Suggested models for catassembly

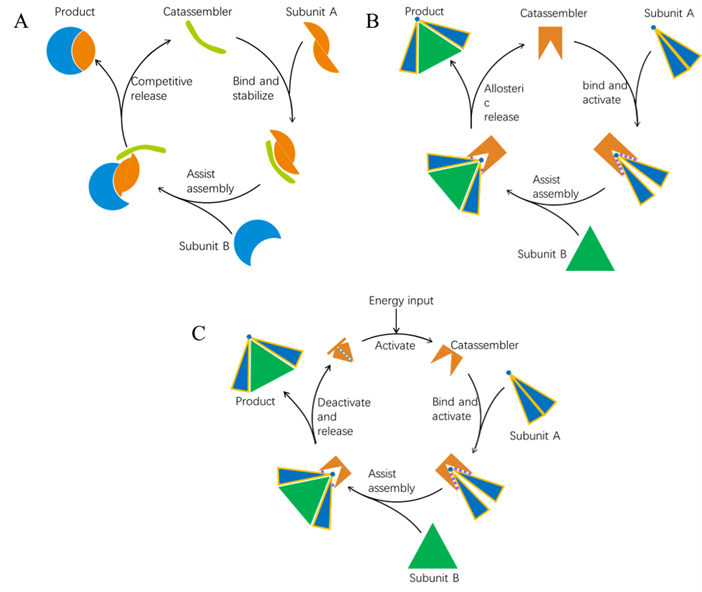

Fig. 2 Three possible models of artificial catassembly. (A) the catassembler act as a protective agent, stabilizing subunit A and accelerating its folding and assembly with subunit B. (B) The catassembler function as an activator. It activates subunit A by exposing the binding sites for subunit B, then the allosteric assembly of A and B releases the catassembler. (C) The catassembler needs to be activated by energy input, then functions as activator for the assembly of subunits A and B.

In the first suggested model (Fig. 2A), the catassembler can prevent subunits A from self-formation through irregular interactions, promoting A and B to bind accurately. Subunit B will replace the catassembler and release it from the complex. Catassemblers can act as activators for molecular assembly as the second model (Fig. 2B), The direct assembly of subunits A and B is hindered due to the concealment of their interaction sites. The introduction of a catassembler initiates the assembly process. The catassembler binds to subunit A in an allosteric manner, thereby exposing the binding sites on subunit A. Subsequently, the activated subunit A interacts with subunit B, forming the complex AB. The binding of A and B weakens the interactions between A and the catassembler, resulting in the release of the catassembler. The catassembler then proceeds to locate a new subunit A and starts a new cycle. Furthermore, catassembly can be powered by external energy as the third model. The energy inputs could be in the form of chemical energy, light, electrical energy, etc. Assuming a catassembler exists in a deactivated state, as shown in Fig. 2C, the energy input can activate the catassembler, initiating a catassembly cycle like Fig. 2B. After the assembly finishes, the deactivated catassembler is then released from the product and can be reactivated by further energy input.

It should be noted that catassemblers differ from co-assembly in that they do not become a part of the final product and can be reused, making catassembly more efficient. The leaving and recycling of catassemblers are crucial in this process. We proposed four possible leaving and recycling mechanisms for catassemblers. 1) The catassembler shares the binding site with other subunits and can be replaced by them at the end of the assembly process (Fig. 2A). 2) The completion of the assembly weakens the binding between the catassembler and the subunits, eventually causing the catassembler to detach (Fig. 2B). 3) The catassembler and final assembly product undergo phase separation (for instance, precipitation), with the product separated into another phase and the catassembler remaining with residual subunits. 4) The recycling of the catassembler is powered by energy input.

Catassembly and catalysis belong to a big family but may have some distinct principles based on the famous essay "More Is Different" by P. W. Anderson. Catassembly could be a much more complicated process based on noncovalent interactions, featuring synergistic multivalent and multicomponent interactions, and long-range feedback. These features are essential to construct hierarchical structures which can eventually emerge new properties and functions, which have yet to be the focus of chemical catalysis. Therefore, it could be highly desirable to make a great effort to develop and even establish fundamental principles, theoretical framework and characterization tools for catassembly. This approach may also initiate reforms in conventional catalysis theory and develop strategies integrating covalent synthesis and noncovalent assembly to construct complex molecular systems.

References

[1] Lei, Z.-C.;§ Wang, X. C.;§ Yang, L. L.; Qu, H.; Sun, Y. B.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.-B.; Cao, X.-Y.; Fan, C. H.; Li, G. H.; Wu, J. R.; Tian, Z.-Q., What Can Molecular Assembly Learn from Catalysed Assembly in Living Organisms? [J] Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53 (4), 1892-1914.

[2] Qu, H.; Tong, T. Y.; Lei, Z.-C.; Shi, P. C.; Yang, L. L.; Cao, X. Y.; Gao, Y. Q.; Hou, Z. H.; Xu, X.; Tian, Z.-Q., Exploring the Theoretical Foundation of Molecular Assembly: Current Status and Opportunities. [J] Sci. Sin. Chim. 2022, 53 (2), 145-173.

[3] Lei, Z.-C.; Wang, X. C.; Qu, H.; Zhou, C.; Li, Z. H.; Yang, L. L.; Cao, X. Y.; Tian, Z.-Q., Some Thoughts About Controllable Assembly (II): Catassembly in Living Organism. [J] Sci. Sin. Chim. 2020, 50 (12), 1781-1800.

[4] Wang, Y.; Lin, H.-X.; Chen, L.; Ding, S.-Y.; Lei, Z.-C.; Liu, D.-Y.; Cao, X.-Y.; Liang, H.-J.; Jiang, Y.-B.; Tian, Z.-Q., What Molecular Assembly Can Learn from Catalytic Chemistry. [J] Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (1), 399-411.

[5] Wang, Y.; Lin, H. X.; Ding, S. Y.; Liu, D. Y.; Chen, L.; Lei, Z. C.; Fan, F.; Tian, Z. Q., Some Thoughts about Controllable Assembly (I) — From Catalysis to Cassemblysis. Sci. Sin. Chim. 2012, 42 (4), 525-547.