Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)

Over the past four decades, our group has focused on developing innovative strategies to overcome the development bottlenecks of SERS and advance its applications in various fields from fundamental research and marketable technology. Some of the key innovative strategies and advancements that our group has developed include:

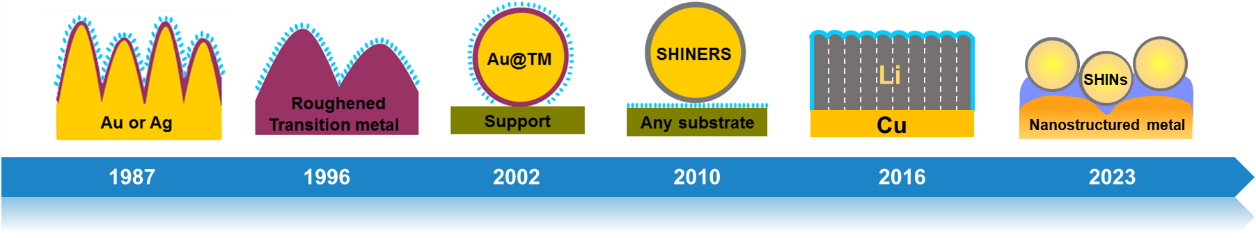

Figure 1. The major strategies of developing SERS in our group over the past four decades.

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a powerful analytical technique that significantly enhances the Raman signal of molecules adsorbed on rough metal surfaces or nanoparticles. Discovered in the mid-1970s, SERS initially sparked optimism for its potential to revolutionize Raman spectroscopy by providing highly sensitive detection capabilities. However, this optimism waned by the mid-1980s due to several key limitations.

One major limitation of SERS is the requirement for specific ‘free-electron-like’ metals, such as Ag, Au, Cu, and Li to exhibit a large SERS effect. Additionally, the metal surface roughness or colloidal size must be on the scale of several tens of nanometers to achieve significant enhancement. This restricts the range of metals and surface structures that can effectively enhance Raman signals, limiting the generality of SERS substrates.

Another significant challenge in the widespread adoption of SERS is the lack of substrate generality and morphology generality of the probed surfaces. The specificity of SERS substrates limits its practical applications in electrochemistry, corrosion analysis, catalysis, and materials science and technology. Furthermore, the requirement for surfaces with specific, often poorly-defined morphologies restricts SERS studies to non-conventional surface structures that may not be readily accepted in the broader surface science community.

Overall, despite its early promise, the limited substrate and morphology generality of SERS have hindered its widespread adoption and practical application in diverse fields. Researchers continue to explore new approaches to overcome these limitations and unlock the full potential of SERS as a versatile and sensitive analytical tool. Therefore, SERS has gone through a tortuous pathway to develop into a powerful diagnostic technique because of the lack of substrate, surface and molecular generalities of SERS has been circumvented primarily by devising and utilizing various nanostructures by our group and others. Now we can the breadth of practical applications of SERS to other materials widely used in energy, surface, medical sciences, and industries.

Focusing on how to breakthrough the SERS limitations, we have developed several pioneered methodologies step by step as below:

1. Electrodeposition of transition metals onto roughened Au or Ag surfaces.

2. Electrochemical roughening of pure transition metal surfaces.

3. Chemical deposition of ultra-thin transition metal layers onto Au nanoparticles.

4. Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS)

5. Electrodeposition of nanostructured Li metal onto Cu surface

6. Depth-sensitive plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (DS-PERS)

Representative achievements:

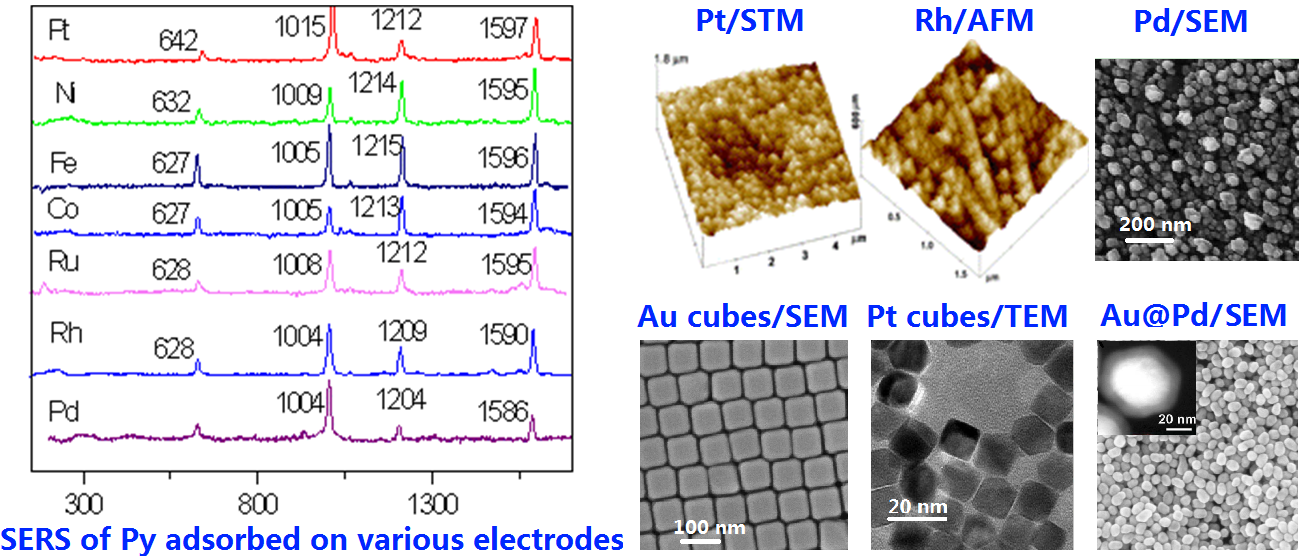

1. SERS on Transition Metal Surfaces (1997-)

That is a remarkable achievement by Tian and his group in advancing surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to impart surface Raman enhancements to transition metals crucial for electrochemistry, catalysis, and interfacial chemistry. Their innovative surface roughening techniques for creating suitable nanostructures enabled the direct generation of SERS on traditionally non-SERS active metals like Pt, Ru, Rh, Pd, Fe, Co, and Ni electrodes. The significant surface enhancements achieved, ranging from one to three orders of magnitude, represent a substantial breakthrough in the field. This research not only expands the scope of SERS applications but also provides valuable insights into the surface properties of transition metals, opening new possibilities for studying their interactions and behaviors at the molecular level.

Three approaches have been developed to obtain SERS-active substrates of transition metals (VIII B): 1) Electrodeposition of transition metals onto roughened Au or Ag surfaces. The obtained substrates display high SERS activities, but the ultra-thin coating layers are non-uniform with pinholes. 2) Electrochemical roughening of pure transition metal surfaces. Raman signals can be directly obtain on pure transition metal electrodes for the first time, but the enhancement is not sufficient enough to investigate some important interfacial phenomena, such as water adsorption. 3) Chemical deposition of ultra-thin (ca. 1–10 atomic layers) transition metals onto Au nanoparticles. The substrates exhibit high SERS activity with uniform morphology and pinhole-free, but it is quite difficult to apply to many other materials, and impossible to work on the smooth surface.

In general, the total surface enhancement factors of transition metals can be substantially boosted up to 102–103, for Pt, Pd, Ru, Rh, Ni and Co, respectively. The obtained good-quality SERS spectra allow us to investigate some crucial interfacial phenomena for the first time, such as the adsorption of water or hydrogen with very small Raman cross-section, on several transition metals (e.g., Pt, Pd and Rh).

Figure 2. SERS on various nanostructured transition metals

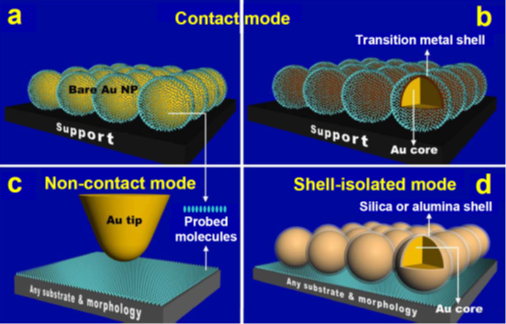

2. SHINERS

In 2010, we have developed a new operation mode, Shelled-Isolated Nanoparticle-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SHINERS), where Au or Ag nanoparticles are coated with ultra-thin shells (about 1 to 5 nm) of chemically inert SiO2, Al2O3 or MnO2 shells. This mode is different from the contact mode of conventional SERS and the non-contact mode of tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS). The Au or Ag cores provides a large enhancement to the probed molecules nearby, while the ultra-thin inert shells isolate the Au or Ag nanoparticles from the ambient environment. The main virtue of such "smart dusts" is the easy preparation and application over surfaces of any material and any morphology, which has been demonstrated with the high quality Raman spectra of probed molecules obtained at various single-crystal surfaces, semiconductors and living cells.

SHINERS method has avoided long-standing limitations (inaccessibility or difficulty) of SERS for the precise characterization of various materials, surfaces and biological samples. The concept of shell-isolated-nanoparticle enhancement may also be applicable to a wider range of spectroscopies, such as infrared spectroscopy, sum frequency generation and fluorescence, etc.

Figure 3. The working principles of SHINERS compared to other modes.

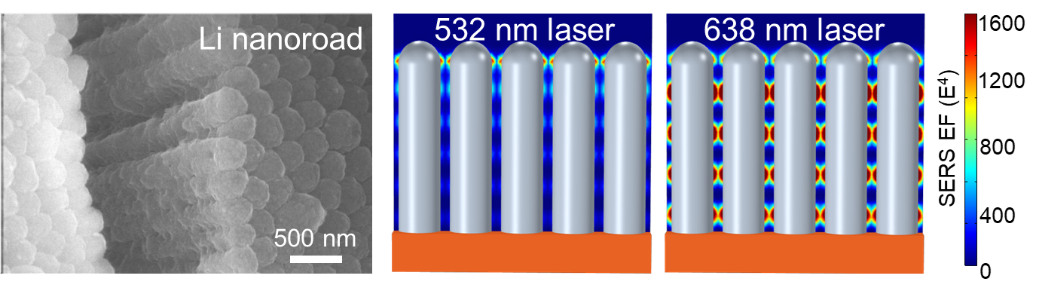

3. SERS from Lithium

Lithium is an s-electron metal which is theoretically expected to support SERS effect. But the experimental investigation of the SERS effect of Li has rarely been reported because of its extremely active surface chemistry in both air and solutions. However, such investigations become increasingly important with stimulation by the active researches in Li-based batteries. In recent years, we have undertaken exploratory efforts to develop high-performance SERS studies based on nanostructured alkali metals. For example, we have successfully designed and prepared Li nanorods on Cu surfaces for obtaining the SERS effect by electrodeposition method in LiPF6-based carbonate electrolytes containing trace amounts of H2O as an additive employed in Li-based batteries. The enhancement factor is calculated for coupled nanorods of ca. 240 nm in diameter, which is about 30 and 7 times for 638 and 532-nm excitations, respectively. The SERS effect of Li may provide a useful and convenient in-situ method to follow the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation process in Li-based batteries without introducing extra SPR-active metals.

Figure 4. SERS-active Li nanoroads and simulations of the electromagnetic field (EF) distribution on Li nanorod under different laser excitation.

4. Depth-sensitive PERS (DS-PERS)

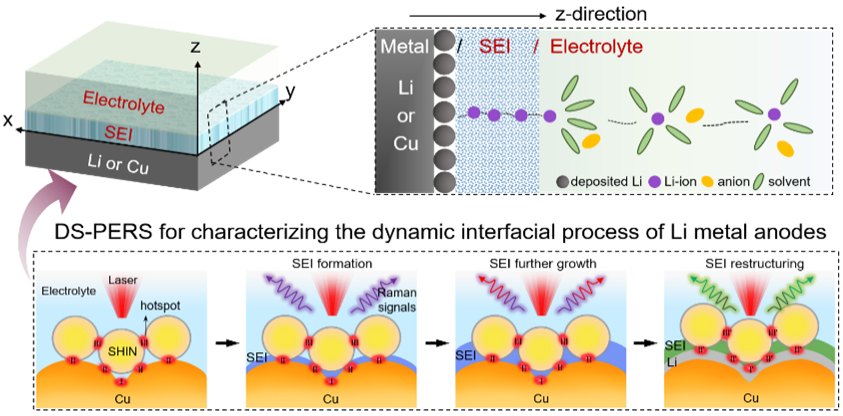

Recently, we have been dedicated to the development of DS-PERS methodology with features of both structure/chemistry-specificity and nanoscale spatial-resolution, which provides opportunities for non-destructive and real-time characterization of intricate nanoscale interphases/interfaces within the diverse fields of energy science and technology.

The first approach is to combine SERS of Cu/Li and SHINERS of shelled-isolated Au@SiO2 nanoparticles (SHINs) to monitor the dynamic formation and evolution of SEI of lithium batteries and the related interfaces in z-direction. By leveraging the integrated plasmonic enhancement of nanostructured Cu/Li and SHINs, we have achieved a depth-sensitive detection of signals from the tens of nanometers thick SEI and from the Cu/SEI, Li/SEI and SEI/electrolyte interfaces during SEI formation at different stages. We have unraveled that a primary SEI is formed on the Cu current collector, followed by restructuring and final formation of SEI on Li. Additionally, we have constructed the chemical mapping of Li-ion solvation structure dictated by the SEI at SEI/electrolyte interfaces. These nanoscale and molecular-level information obtained by DS-PERS unravel the profound influences of the metallic Li in modifying the SEI formation and in turn the roles of SEI in regulating the desolvation chemistry of Li-ion and the following Li deposition.

Figure 5. Resolving the complex interfacial process of Li metal anodes by DS-PERS.

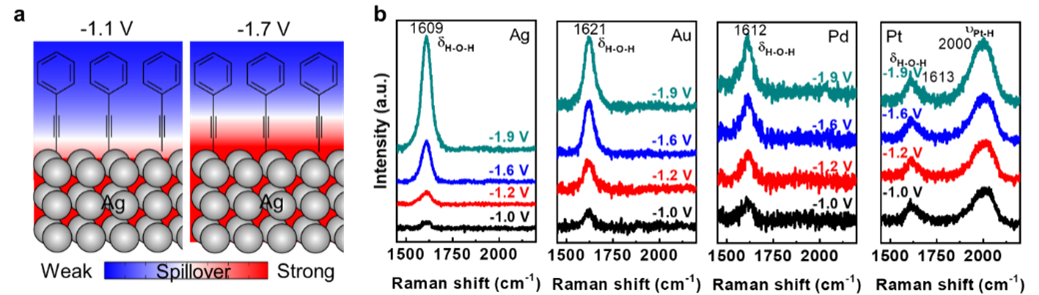

The second approach is to develop a plasmonic molecular ruler strategy that combines in-situ electrochemical PERS with theoretical analysis to elucidate the specific characteristics of interfacial electronic spillover at electrochemical interfaces under very negative potentials. Utilizing specific molecules adsorbed onto metallic electrodes (Pt, Pd, Au, and Ag) as molecular rulers, we have achieved angstrom-level spatial resolution in measuring electron spillover from the electrode to the electrolyte. Notably, we observed abnormal spectral features in the libration (network motion) of interfacial water and believed to result from the synergy between spilled electrons and surface plasmons (SPs), having a sharply gradient distribution. It may spark a new idea regarding the creation of special interfacial structures and processes of electrochemical interfaces unprecedentedly.

Figure 6. The plasmonic molecular ruler strategy to investigate interfacial electronic spillover at electrochemical interfaces under very negative potentials.

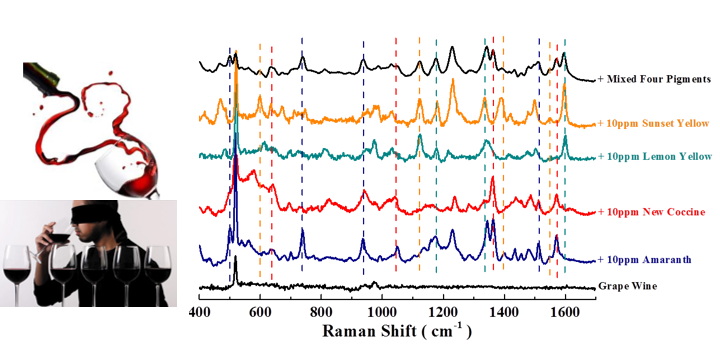

5. Applications of SERS/SHINERS in food safety and public health

SERS/SHINERS has a broad and diverse range of chemical applications from electrochemistry and catalysis, single-molecule detection, sensing and trapping, to solid-phase synthesis, to bioanalytical applications. Very recently, the emerging of portable Raman instruments open a new window for SERS/SHINERS applications: on-site fast detection with high sensitivity towards food & medical safety, environmental protection, and social & national security. Our startup company mainly focus on the application of SERS to food & medical safety, such as the pesticides in fresh foods or teas, the illegal additives in processed foods and healthy products.

Figure 7. Applications of SERS/SHINERS in food safety.

6. AI-driven SERS

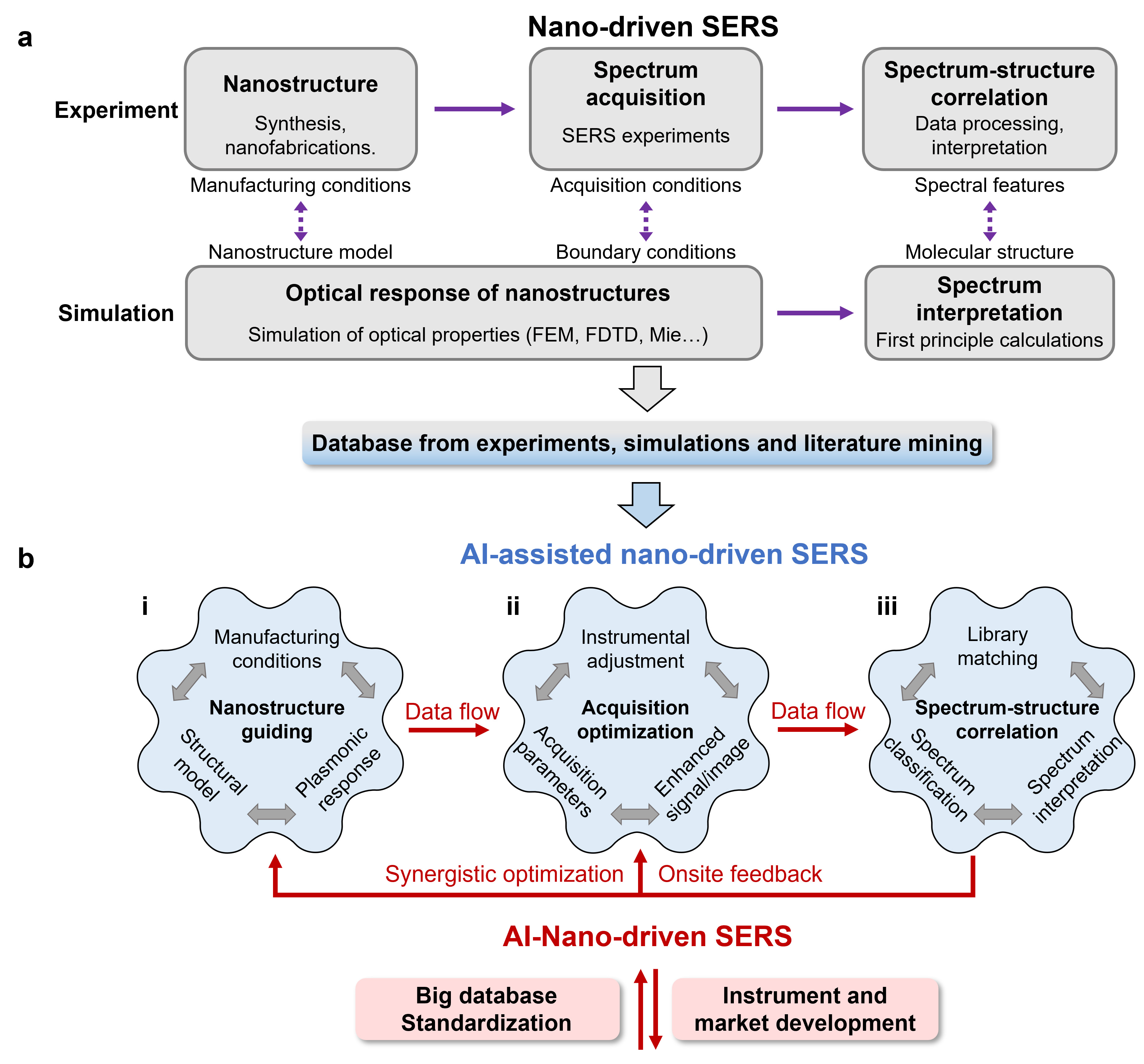

The ultra-high sensitivity of SERS strongly depends on the shape and size of metal nanostructures, especially the sub-nanometer distances between nanoparticles. This makes it difficult to achieve consistency and stability when preparing SERS-active structures, severely limiting the standardization of SERS processes and detection repeatability. This presents enormous challenges for large-scale market production. Currently, the SERS technology workflow primarily relies on comparing experimental and theoretical results, with limited explorable parameter space and high trial-and-error costs, making it difficult to overcome these bottlenecks long-term. In fact, this represents a common challenge faced by many precision-dependent nanotechnologies when advancing toward market applications.

We propose that AI technology has the potential to solve these problems. However, current AI+SERS research is still at the stage of AI-assisted SERS research and can be divided into three categories: design and preparation of nanostructures, optimization and control of intelligent instrument systems, and analysis of Raman spectral-molecular structure relationships. The latter category accounts for more than 90% of current AI+SERS research, while the first two directions have received minimal attention, and there is an even greater lack of interaction between all three areas. There is an urgent need to implement spontaneous internal data exchange and generation that drives autonomous optimization with real-time feedback decision-making. This would integrate the three directions into a self-driven closed-loop AI-Nano-driven SERS research paradigm. Such a breakthrough would likely enable the standardization and intelligent development of SERS technology, thereby strongly promoting its market expansion.

Figure 8. Workflow of AI-assisted and AI-driven SERS.

7. A half-century historical review of SERS

2024 marks the 50th anniversary of the discovery of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). In collaboration with over 40 research groups from around the world, we have authored a comprehensive review article reflecting on the half-century history of SERS. Using methodological development as the main narrative thread, we have divided the 50-year evolution of SERS into four critical phases: the foundation period (mid-1970s to mid-1980s), the period of decline and continued exploration (mid-1980s to mid-1990s), the nano-driven explosion period (mid-1990s to mid-2010s), and recent advancements (mid-2010s to present).

Throughout this developmental journey, SERS has been intimately connected with progress in nanoscience and plasmonic photonics. The establishment of its experimental and theoretical foundations represents the collective wisdom and contributions of numerous scientific pioneers. Particularly noteworthy is how SERS technology has continuously evolved to generate new branches, such as Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS) and Shell-Isolated Nanoparticle-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SHINERS). These innovative approaches have not only enriched the SERS family but also provided novel solutions to overcome technical bottlenecks, significantly expanding the applicable range of materials, morphologies, and molecules. These developments have propelled SERS into a multifunctional technology with extensive application prospects.

References:

1. Tian, Z.-Q., et al. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering: From noble to transition metals and from rough surfaces to ordered nanostructures. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 106, 9463–9483 (2002).

2. Tian, Z.-Q., et al. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering from transition metals with special surface morphology and nanoparticle shape. Faraday Discussions. 132, 159–170 (2006).

3. Li, J.-F. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy using gold-core platinum-shell nanoparticle film electrodes: Toward a versatile vibrational strategy for electrochemical interfaces. Langmuir 22, 10372-10379, (2006).

4. Tian, Z.-Q., et al. Expanding generality of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy with borrowing SERS activity strategy. Chemical Communications, 3514–3534 (2007).

5. Wu, D.-Y., et al. Electrochemical surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of nanostructures. Chemical Society Reviews, 37, 1025–1041 (2008).

6. Li, J.-F., et al. Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature, 464, 392–395 (2010).

7. Li, J.-F., et al. Surface analysis using shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature Protocols, 8, 52–65 (2013).

8. Ding, S.-Y., et al. Nanostructure-based plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for surface analysis of materials. Nature Reviews Materials, 1, 16021 (2016).

9. Tang, S., et al. An electrochemical surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic study on nanorod-structured lithium prepared by electrodeposition. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 47, 1017–1023 (2016).

10. Li, J.-F., et al. Core-Shell Nanoparticle-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Chemical Reviews, 117, 5002–5069, (2017).

11. Panneerselvam, R., et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: bottlenecks and future directions. Chemical Communications, 54, 10–25 (2018).

12. Gu, Y., et al. Resolving nanostructure and chemistry of solid-electrolyte interphase on lithium anodes by depth-sensitive plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature Communications, 14, 3536 (2023).

13. Gu, Y., et al. Nanostructure-Based Plasmon-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Strategies for Characterization of the Solid-Electrolyte Interphase: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 127, 13466–13477, 2023.

14. Yi, J., et al. Unveiling the Angstrom scale interfacial electronic structure through metal/electrolyte interfaces by plasmonic molecular rulers. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 147, 29468 (2025).

15. Yi, J. et al. AI–nano-driven surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for marketable technologies. Nature Nanotechnology, 19, 1758–1762, (2024)

16. Yi. J. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: a half-century historical perspective. Chemical Society Reviews, 54, 1453-1551, (2025)